Brain development during adolescence is fundamentally a story of connections.

Around age 9 or 10, hormonal changes kick off a period of intense learning and development, when brain cells form, strengthen, and streamline connections in response to our experiences more rapidly than in any period of life after early childhood.

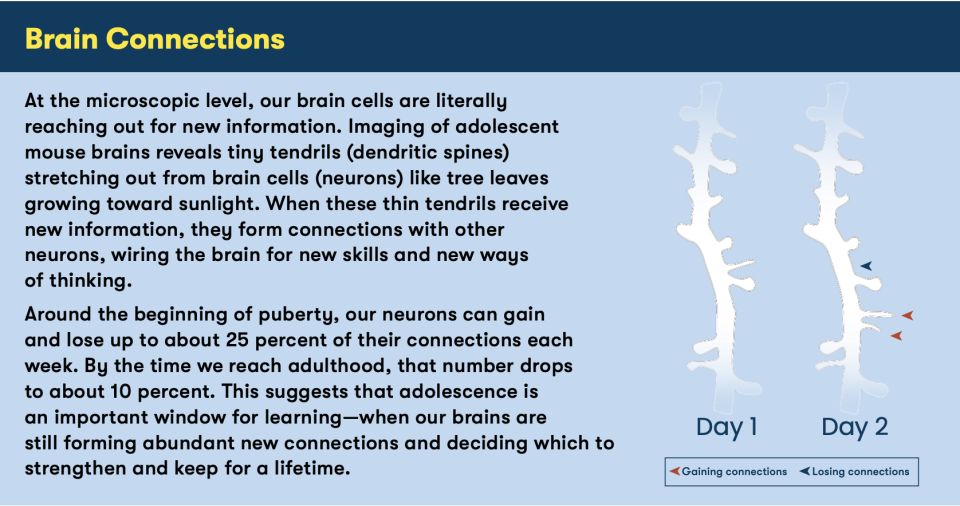

Activity increases especially in the brain networks that propel us to explore the world, learn from our mistakes, and connect with others in new ways. In turn, these new experiences prompt our brain cells to connect with other neurons in ways that help us adapt to new events and new information. These neural connections become stronger the more we use them, while unused connections are pruned away, helping the brain become more efficient at acquiring and mastering new skills and new ways of thinking.

This brain-building learning happens through direct experiences in our environments and interactive, responsive relationships—with our families and peers, in our classrooms and neighborhoods, in community activities, and even online. The resources, opportunities, and experiences we as adults provide in and out of school can help young people’s brains build the extensive networks of connections that will manage the complex knowledge and behaviors needed to navigate adulthood.

Learning by Exploring the World Around Us

One of the networks that changes significantly with the increase in hormones and dopamine at the beginning of puberty is the “reward system” in our brain. Heightened activity in this system increases the feeling of reward we get from exploring the world, taking risks, and learning from the results.

Meanwhile, the network of brain regions that make up the “social brain” also changes during adolescence. These changes help us tune into social and emotional cues, like facial expressions or social rejection and approval, and increase our desire to earn respect and contribute to others. It also enables us to learn the nuances of changing social contexts in ways that help prepare us for adult relationships.

The prefrontal cortex (the region of the brain that orchestrates critical thinking and behavioral control) undergoes its most rapid period of development during adolescence. It builds on many other systems within the brain to manage our responses to the flood of new information and intensifying emotions. Engaging with other people and our environment and learning from our successes and our mistakes, known as “action-based learning,” helps shape the prefrontal cortex by strengthening the connections within it and between it and other brain networks. We learn through repeated practice—which includes trying and sometimes failing—what is adaptive and appropriate in different situations and how to guide our behavior accordingly, in ways that equip us to pursue new forward-looking goals.

When adults provide youth with opportunities to try new things, to practice navigating emotions, and to learn from failures along the way, it helps build the brain connections that we all need to grow into healthy, thriving adults.

Policies, Experiences, and Mindsets Shape the Connecting Brain

Although we can continue to learn new skills and behaviors as adults, the adaptability of the brain during adolescence means that these connections are much more likely to form quickly in response to experiences. The extent of these changes make the adolescent years a critical window when investments in the right policies and programs for youth can shape long-term positive development.

Likewise, this makes the adolescent years a time when negative experiences including racism, other forms of discrimination, poverty, or abuse can create steeper hills for young people to climb toward a healthy adulthood. When adults ensure that all young people, especially those who have experienced earlier adversity, have what they need along their journey, they can build the skills and capacities they need to thrive as adults. This includes opportunities to explore and take healthy risks, to connect with and contribute to those around us, to make decisions and learn from the outcomes, to develop a healthy sense of identity, and to rely on support from parents or other caring adults.

Understanding how and why the brain develops during adolescence lets us provide the support young people need to build healthy connections—in their world and within their brains—that will help our youth and our communities thrive.